Aujourd’hui, Maman est morte

“Aujourd’hui, maman est morte” (Today, mom died) *

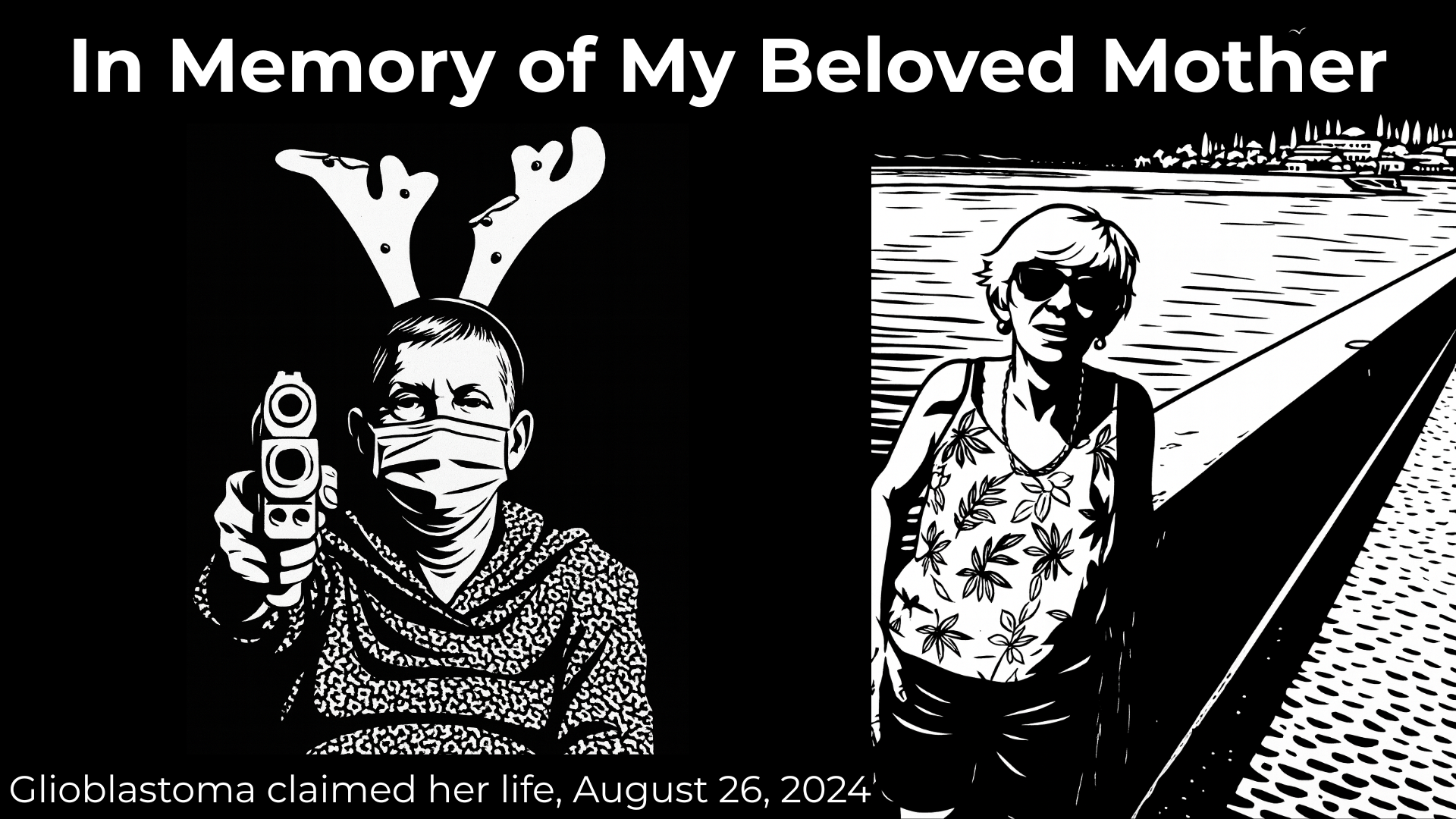

Exactly one year ago my mum died from glioblastoma.

It took me time and energy to process and decide whether I wanted to share this story or not. But I believe it might resonate with hundreds (if not thousands) of other families suffering from the direct (and side) effects of brain tumors. I also wanted to leverage this dark anniversary to pay homage to my mum while trying to raise awareness about end-of-life treatment in French medical institutions. This piece is personal, but I hope it can help others and describe why better end-of-life support is needed in France.

As I will recount our journey, it’s crucial to remember that the true depth of suffering lay with my mum, a pain far greater than anything we experienced.

The Diagnosis: A Glioblastoma Journey Begins

This is the story of Orev, my 64-year-old mother, whose journey with glioblastoma began quietly but ended tragically. Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), one of the most aggressive forms of brain cancer, progresses rapidly and carries a devastating prognosis: most people live an average of 12 to 18 months after diagnosis.

In early May 2022, a small tumor was discovered in her corpus callosum—the thick band of nerve fibers connecting the two brain hemispheres. Its critical location made surgical intervention impossible. The first MRI was ambiguous, showing something unusual but inconclusive. Later that month, a biopsy confirmed the devastating diagnosis: GBM.

The news had to be delivered by phone, and I was the one who told her. It was a terrible moment for both of us, filled with confusion, heartbreak, and a profound sense of helplessness. I’ll never forget that conversation; it was a responsibility placed upon me by the neuro-oncologist, a decision I still grapple with, despite my mother’s later appreciation that it came from me, not a ‘cold stranger’.

Early symptoms, leading Orev to ask for an MRI scan, were persistent migraines, headaches, blurred memory, and a sense of “mental fog”. Despite the short median survival time for GBM patients—around 12 to 15 months—Orev “defied the odds,” surviving two years and three months. Her initial treatment involved six weeks of radiation combined with Temodal (temozolomide, a standard chemotherapy drug), followed by additional chemotherapy cycles. The first chemotherapy began in August 2022. Her MGMT methylation, a clinically relevant prognostic marker, was low (~13%), indicating lower survival and a reduced response to Temodal.

After this initial phase, she had to wait six months before assessing the tumor’s progression, due to difficulties in performing MRI scans after irradiations. In January 2023, the follow-up MRI revealed disease progression, prompting the restart of a new chemotherapy treatment. In March, she began experiencing a steep cognitive decline, and by April-May 2023, her condition required urgent hospitalization and corticosteroid treatment to manage a brain edema.

Beyond the medical complexities, Orev’s diagnosis also plunged our family into an intense emotional landscape, exposing deeply personal coping mechanisms and unforeseen challenges.

Navigating Grief and Family Dynamics.

In July 2022, with my help and support, Orev subscribed to Dignitas in Switzerland, contemplating assisted suicide to avoid her biggest fear: a complete loss of cognitive functions and autonomy. However, due to my father’s (Roger) opposition, she ultimately did not pursue this option and suffered that exact situation two years later.

For a woman accustomed to control and independence, the fear of death and loss of autonomy was overwhelming. With a history of depression, Orev sank deeper into despair as her cognitive abilities eroded. Losing the ability to count, reason, and recall memories—the very faculties defining her—was devastating.

The emotional burden on the family was immense, and her decline deeply affected all of us. She had been the family’s anchor, decision-maker, and central figure. Slowly, we began to lose her, and with it, the family unity. Two sides slowly appeared within the family, two coping strategies, and ultimately two non-compatible groups that grew further apart over time.

Her husband, Roger, and daughter, Laure, who lived nearby and interacted daily, met the diagnosis with a form of denial—a defense against the painful reality of losing their beloved wife/mum and family cornerstone. Even though they documented themselves and understood the grim reality of Orev’s impending death, they held onto false hope and refused to accept it. This denial was accompanied by a total lack of communication. To my knowledge, they almost never discussed what was going to happen. They gave all the energy they had, this is obvious, but it did not fully help them face reality, act properly, and, most importantly, plan and accompany her psychologically through this horrific journey.

On the other hand, my brother, Naturel, and I were both totally supportive of her initial end-of-life choices. We understood that she would decline and die in the coming year (or two if lucky). But both of us were living in distant places and were not the first line of helpers. Naturel faced the inevitable in two phases: at first, he offered total support—he even moved to our parents’ place for a month and half. But as tension grew, he shifted into anticipatory grief, eventually withdrawing completely for the six months leading up to her death.

Initially, I found myself in the middle, struggling to mediate and communicate amidst growing tensions. At the beginning, this communication game was okay, translating medical and familial matters to both sides. On one hand, I understood the true meaning of the diagnosis (I might have actually been too pessimistic, reading all the literature I could find on the topic), and on the other hand, I was emotionally protected by the physical distance and my personal context.

However, as Orev’s illness progressed, these emotional and psychological struggles quickly translated into tangible social and practical challenges that further tested our family’s resilience and exposed critical gaps in support systems.

Beyond the Emotional Toll: Social and Practical Realities

As Orev’s condition worsened, the family dynamics shifted dramatically. Roger, the primary caregiver, started to experience some burnout (never officially diagnosed or discussed). The emotional and physical toll, compounded by his reluctance to seek external help, significantly impacted his health. The family isolated themselves from external support, exacerbating their strain.

Fortunately, financial concerns were minimal (in part) due to France’s robust healthcare system, enabling the family to focus solely on Orev’s care. However, as her cognitive abilities declined, social interactions decreased, weakening the family’s once-strong bond.

A pivotal conflict arose in May 2023 when Orev became severely impaired and nearly comatose (a strong edema had formed around the tumor). Roger and Laure refused to listen to Naturel and did not want to call the neuro-oncologist, remaining in denial about her rapidly deteriorating condition. I intervened, calling the hospital with prior approval from all family members. Upon arrival at the hospital, the neuro-oncologist confirmed the urgency, immediately administering corticosteroids to reduce the brain edema caused by the tumor. Only after Orev’s cognitive and physical state stabilized did Laure begin to blame me because the family did not wish to cancel a planned vacation the coming week. Though the hospitalization (which had actually been validated by all two weeks earlier) likely saved Orev’s life, I was blamed for disrupting their plans. This highlights the painful tensions that denial and fear can create.

It is also following that specific event that Orev and Roger decided to abandon the idea of assisted suicide in Switzerland. Then, Orev’s state was stable for a little while. She had a third line of treatment, which required a PICC (peripherally inserted central catheter) line and very recurrent visits to the hospital. A difficult period initiated… more despair, helplessness, and boredom, but mostly a veritable feeling of what was inevitably coming soon.

In May 2024, Orev experienced total loss of speech, accompanied by a fall that resulted in a broken right arm. Surgery was not an option due to her fragile condition.

After May 2024, everything collapsed. Orev was essentially locked inside her body, often in visible pain, yet receiving little more than a Doliprane once or twice per day—only if she “appeared to be suffering,” according to Roger. Until August 2024, they resisted providing her with strong pain relief. In those final days, as she could no longer swallow food and was visibly fading, she was finally administered more potent drugs—though not continuously. Only then was her pain briefly alleviated.

On Monday, August 26, 2024, at 6 am, she passed away in her bedroom, holding the hand of her beloved husband, finally relieved from all the pain.

My mother’s passing, while bringing an end to her suffering, marked the beginning of a profound reflection for me. Her two-year battle not only revealed the devastating nature of Glioblastoma but also illuminated severe shortcomings in how our healthcare system, particularly in France, addresses terminal illness and end-of-life care.

Beyond the Diagnosis: Advocating for Change in Terminal Care

In the end, and in my opinion, it could have been different. She could have gone in better conditions. She could have suffered less. If the medical system focused slightly more on the human side. There are several aspects that should be improved in the way the medical system is “treating” patients who face inevitable prominent death:

- Inadequate Communication from Medical Professionals: A significant challenge throughout this ordeal was inadequate communication from medical professionals. Despite my neuroscience background, I found myself bearing the responsibility of informing my mother about her terminal diagnosis—a task that medical professionals should have compassionately handled. This disrupted communication was present until the end. It was often evident that my parents did not understand much of what the neuro-oncologist had been discussing during their interviews. A good solution they found was to record and re-listen later on.

- Lack of Dignified End-of-Life Options in France: Early in her illness, Orev considered assisted suicide through Dignitas in Switzerland, subscribing to their program. Roger resisted this choice, and eventually, he insisted enough so that the idea was abandoned. As Orev’s disease progressed and she lost autonomy, Roger acknowledged that assisted suicide might have been appropriate, if the logistics were easier. This experience highlights a critical gap in France’s healthcare system: the absence of dignified end-of-life options for terminally ill patients. Relying on an external, unvalidated, unpractical foreign option did not help the decision, leaving Orev without a truly dignified choice.

Beyond Awareness: A Call to Action for Systemic Healthcare Changes

Glioblastoma’s impact is devastating, most profoundly affecting the patient. While I’ve described the immense pain and challenges our family faced, it is the unimaginable depth of my mum’s suffering that truly compels this call to action. Orev’s journey, tragically cut short by GBM and the limitations of our current healthcare system, illustrates the urgent need for systemic change in France’s healthcare approach. But we don’t have to accept the status quo.

Here’s how you can help create a more compassionate and dignified future:

- Raise Awareness: Share Orev’s story and this article with your network. Talk to your friends and family about Glioblastoma and the critical importance of dignified end-of-life options. The more we speak about it, the more visible the need for change becomes.

- Support Research: Contribute to organizations funding Glioblastoma research. Every donation, no matter the size, fuels the scientific breakthroughs that could lead to better treatments and, one day, a cure.

- Advocate for Policy Reform: Contact your elected officials in France. Urge them to reconsider current policies surrounding end-of-life care, pushing for legal, dignified options such as assisted suicide or euthanasia for terminally ill patients. Your voice can influence critical legislative changes.

- Improve Medical Communication: Support initiatives that provide better training for healthcare professionals on delivering difficult news with compassion and clarity. Demand transparency and comprehensive explanations of medical conditions and prognoses.

- Eliminate Pseudoscience: Insist on evidence-based treatment plans to uphold the integrity of medical care and protect vulnerable patients from false hope and ineffective remedies.

- Preserve Family Bonds: Recognize that Glioblastoma does not only destroy the patient’s body, but often fractures family relationships under the weight of stress, anticipatory grief, and role reversals. This can be mitigated by the presence of a neutral third party—such as a psychologist, social worker, or trained volunteer—who supports families emotionally, accompanies them to medical appointments, and helps maintain communication and cohesion during the most difficult stages.

Glioblastoma is a cruel disease, with profound impacts reaching far beyond the individual diagnosed. Through increased awareness, improved medical communication, and compassionate end-of-life care options, we can provide dignity and meaningful support to those facing this formidable challenge.

I hope these words may have an impact, or at least may help one person who is in a similar situation to feel slightly less alone. Good luck to everyone impacted by this disease and similar conditions.

And most importantly: Je t’aime Maman!

- “Aujourd’hui, maman est morte. Ou peut-être hier, je ne sais pas” is the Incipit from the novel The Stranger by Albert Camus (1942). It translates as: “Today, mom died. Or maybe yesterday, I don’t know.”